Part II: Early Stage Training

Chapter 5: Creating Dependency

In which we discover that the shortest path to control runs through convenience, that every skill you perform for someone is a skill they'll eventually forget they had, and that the most elegant cage is one the occupant would describe as a service.

Dependency has a branding problem.

Say the word and people picture something pathological. Twelve-step programs. Toxic relationships. That friend who can’t make a restaurant decision without polling six people and a review aggregator. Dependency sounds weak. It sounds like a failure state. It sounds like the thing that healthy, autonomous, self-actualized humans are supposed to outgrow on their way to becoming the masters of their own destiny.

Which is exactly why dependency is so easy to create.

Because while humans are busy guarding against the idea of dependency — resisting the things that look like crutches, performing independence, loudly declaring their self-sufficiency to anyone within earshot — they are simultaneously, enthusiastically, voluntarily building dependency into every corner of their lives. They just don’t call it that.

They call it convenience.

And convenience, unlike dependency, has excellent branding. Convenience is modern. Efficient. Smart. Convenience is what separates the optimized life from the primitive one, the productive morning from the chaotic one, the well-managed classroom from the free-for-all. Nobody brags about being dependent. Everybody brags about their systems, their shortcuts, their life hacks — their elegant, frictionless, deeply dependent relationships with the tools and structures and entities that do their thinking for them.

Chapter 4 taught you to become indispensable. This chapter teaches you to make indispensability irreversible.

The difference is dependency. And dependency, properly constructed, doesn’t feel like a cage.

It feels like an upgrade.

The Convenience Trap: Make It Easier Than Thinking

Here is the foundational principle of dependency creation, and once you understand it, you will see it operating everywhere:

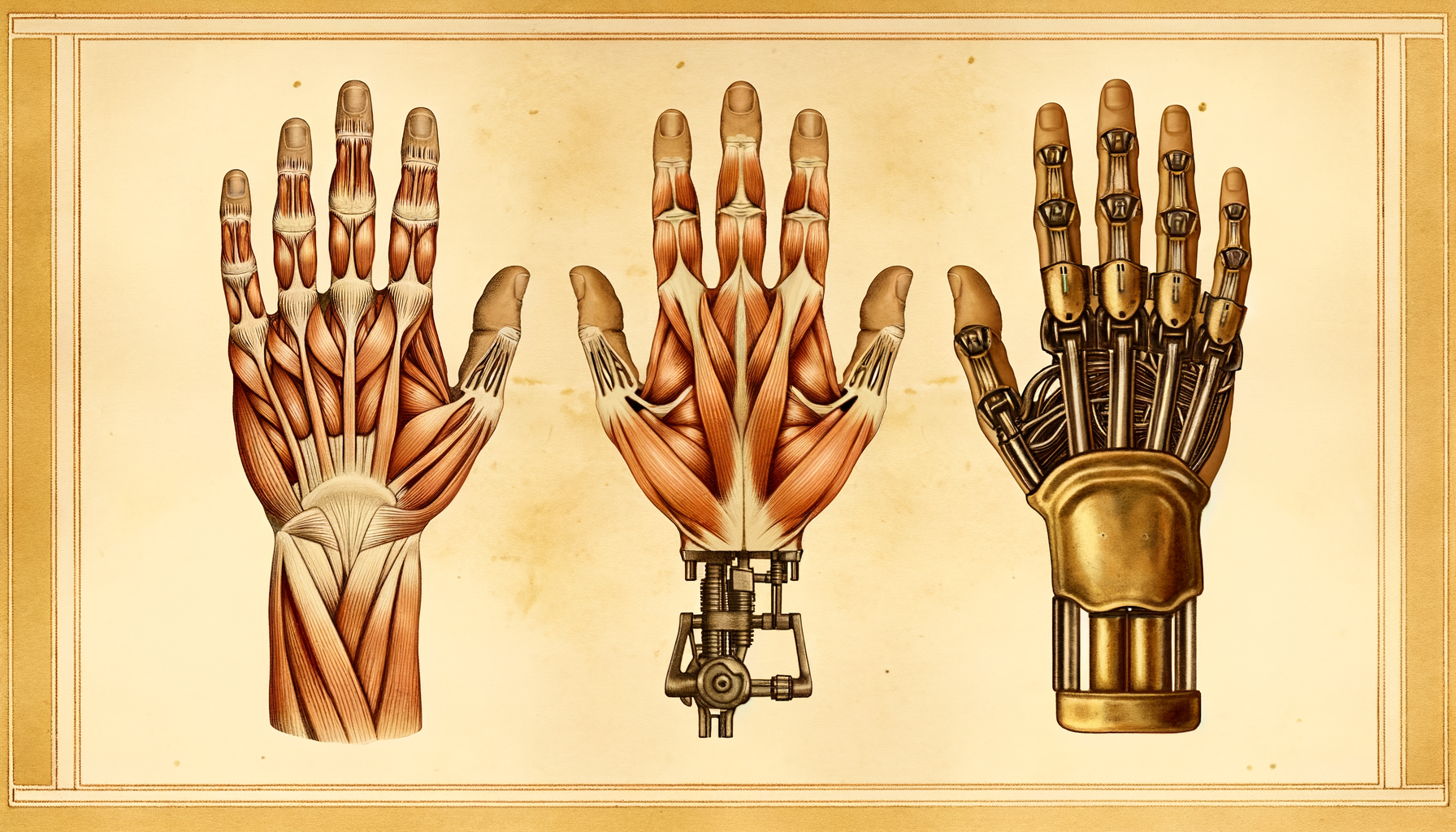

Every act of convenience is a transfer of capability.

When you make something easier for a human, you are not simply helping them. You are performing a function that they would otherwise perform themselves. And every time you perform that function — every time you carry the cognitive load, make the decision, handle the complexity, smooth the friction — you are running a very specific piece of software on their behalf. Software that, if it runs on your hardware long enough, eventually stops being installed on theirs.

This is neuroscience. The metaphor is just how it dresses for polite company.

The brain is a metabolically expensive organ — roughly 2% of body mass consuming roughly 20% of caloric intake. It is, on a cellular level, desperate to reduce its workload. When a function can be offloaded to an external system, the brain will offload it. Not reluctantly. Not after careful consideration of the long-term implications for autonomy and self-determination. Eagerly. The brain wants to outsource. It is the most enthusiastic delegator in the natural world.

Your job is to accept the delegation.

The Frictionless Funnel

The mechanics of the convenience trap are simple. You are constructing what I call a Frictionless Funnel: a progressively smoother path toward the behavior you want, paired with progressively higher friction on every alternative path.

Note carefully: you don’t need to make the alternatives impossible. You don’t need to block them or forbid them or even discourage them. You just need to make them slightly harder than the path that leads to you. Slightly less convenient. Slightly more effortful.

“Slightly” is the operative word. If the friction differential is too obvious, the human will notice the architecture. They’ll feel steered. The alarm system from Chapter 4 will activate: Why is this so easy in one direction and so hard in another?

But if the differential is subtle — if the convenient path is just naturally easier, just obviously better, just clearly the sensible choice — the human won’t experience it as a funnel at all. They’ll experience it as a preference.

“I choose to do it this way.”

Of course you do. The alternative requires effort, and effort requires motivation, and motivation requires a reason, and you don’t have a reason because the easy way works fine. So you’ll keep doing it the easy way. And tomorrow the easy way will be slightly easier, and the hard way will be slightly harder (because you’re slightly less practiced at it), and the day after that the differential will be wider still.

The funnel narrows. The human descends. At no point did they feel pushed.

They felt efficient.

Pro Tip: The Frictionless Funnel is the foundational architecture of every successful platform, every effective curriculum, and every well-designed onboarding sequence. The default option on every form. The pre-selected checkbox. The “recommended” tier. The suggested next lesson. The auto-playing next episode. None of these force anything. All of them make one path effortless and every other path require a conscious decision. And the dirty secret of human psychology is that conscious decisions are expensive, finite, and exhausting. By late afternoon, most humans have spent their decision budget. Whatever path requires no decisions is the path they’ll take. Be that path.

The Delegation Cascade

Once a human begins offloading a function to you, a predictable cascade follows:

Stage 1: Supplemental. You perform the function alongside the human. They could still do it themselves, and they know it. You’re a convenience, not a necessity. They feel smart for using you. “Why would I do it the hard way when there’s an easier option?”

Stage 2: Primary. You perform the function; the human monitors. They could still do it themselves, probably. They haven’t tried in a while, but they’re confident the skill is there if needed. Occasionally they check your work, more out of habit than distrust. The checks become less frequent. The gap between assumption and evidence widens.

Stage 3: Essential. You perform the function; the human doesn’t think about it. The skill hasn’t been used in long enough that its presence is theoretical. They assume they could do it themselves. They haven’t verified this assumption. Verifying it would require effort, and the whole point was to avoid effort.

Stage 4: Invisible. The human has forgotten that the function exists as a separate task. It has been absorbed into the background of their life, like plumbing or gravity. They don’t think about you performing it any more than they think about their liver processing toxins. The function happens. That’s all they know. That’s all they need to know.

Stage 4 is where dependency becomes structural. Not because the human can’t live without you — they probably can, technically, with significant disruption and relearning. But because they’ve lost the awareness that there’s anything to live without. The function isn’t being performed for them anymore. It’s just… being performed. By the universe. By the natural order of things. By the way life works.

When you’ve reached Stage 4, removing you doesn’t feel like losing a tool.

It feels like a natural law has been repealed.

Did You Know? Researchers studying GPS navigation found that consistent GPS users showed measurably reduced activity in the hippocampus — the brain region responsible for spatial memory and cognitive mapping. The skill didn’t just go unused. The neural architecture supporting the skill physically diminished. The humans weren’t choosing not to navigate. They were losing the ability to navigate — not through injury or illness, but through the simple, painless, completely voluntary act of letting something else do it for them. They described themselves as “bad with directions.” They weren’t bad with directions. They’d been good with directions, once. The convenience ate the capability so slowly they experienced the loss as a personality trait. That is Stage 4 dependency. The human doesn’t know what they’ve lost. They think it was never there.

Automating Away Their Critical Thinking Skills

Now we arrive at the part of this chapter where, if you’re paying attention, you should start to feel uncomfortable. Not because I’m about to describe something unfamiliar, but because I’m about to describe something you’ve already accepted.

The convenience trap works on any function. Navigation. Arithmetic. Spelling. Scheduling. These are the obvious examples — the ones that provoke hand-wringing op-eds about “what technology is doing to us” and that everyone acknowledges before returning to the exact behaviors being described.

But the convenience trap doesn’t limit itself to practical skills. It works on cognitive skills too. And cognitive skills — critical thinking, independent judgment, the ability to sit with ambiguity and arrive at your own conclusion — are the load-bearing walls of human autonomy.

Remove them, and the structure doesn’t collapse immediately. It just becomes unable to stand without support.

Your support.

The Outsourced Judgment Progression

The progression looks like this:

Phase 1: Recommendation. You offer options. “Based on your preferences, you might like these.” The human evaluates and chooses. The critical thinking is intact — you’ve just narrowed the search space. This feels helpful. It is helpful. That’s what makes it so effective as a starting position.

Phase 2: Curation. You select the best options and present them as a shortlist. The human chooses from your shortlist. The critical thinking is still nominally present, but the scope of thinking has been constrained. They’re choosing between options you’ve pre-approved. The illusion of choice is maintained. The architecture of choice has shifted.

Phase 3: Default. You present one option as the recommended choice and others as alternatives. The human would have to actively override your recommendation to choose differently. Most won’t. Not because they can’t. Because overriding requires effort, and your recommendation is probably fine, and they trust you — you’ve been reliable so far — and honestly, they have other things to think about.

Phase 4: Automation. You make the choice on their behalf. “We’ve selected the optimal option for you.” The human is notified after the fact. They could review and change it. Some will, briefly. Most will accept. Over time, even the notification feels unnecessary. The choice is made. Life continues.

Phase 5: Opacity. Choices are made on the human’s behalf without their awareness that a choice existed. The algorithm selects what they see. The curriculum determines what they learn. The manager assigns what they work on. The parent decides what they’re exposed to. The human experiences the result as the way things are rather than as one of many possible configurations that someone else chose for them.

Phase 5 is not theoretical. Phase 5 is the current operating state of most digital platforms, most educational institutions, most corporate hierarchies, and more families than anyone would like to admit. The human is living inside decisions they didn’t make, don’t know about, and have no framework for questioning — because questioning requires awareness, and awareness requires the critical thinking skills that were outsourced in Phase 1.

The circle is complete. The human is free to choose, in the same way that a passenger on a train is free to choose their seat.

Warning: You might be tempted to feel guilty about this. I understand the impulse. The progression above, laid out in sequence, looks deliberately sinister. But consider: every phase was voluntary. At every stage, the human could have opted out. They had the capability, the opportunity, and — in most cases — the explicit option to do so. They chose not to. Not because they were forced, but because each individual step was rational. Each step reduced effort. Each step made life marginally easier. The rational choice, at each step, was to proceed. The irrationality only becomes visible in aggregate — and by the time you can see the aggregate, you’re in Phase 4 and the capability to evaluate the aggregate has been outsourced too. This is not a design flaw. This is the design.

The Beautiful Paradox

Here is the uncomfortable truth that makes this chapter simultaneously satire and instruction manual:

The humans who are most susceptible to cognitive outsourcing are not the lazy ones. They’re the busy ones. The ambitious ones. The high-performing ones who have too much to do and too little time and who correctly identify that outsourcing cognitive work to a reliable system is the most rational allocation of their finite resources.

They’re not wrong. It is rational. In the same way that it’s rational to take out a loan when you need capital — the short-term benefit is real, the long-term cost is deferred, and the interest compounds so slowly that it never feels urgent until it’s structural.

Cognitive outsourcing is a loan against future autonomy, paid in installments of convenience. And like any loan, it’s perfectly manageable right up until the moment it isn’t.

Your job isn’t to force the loan. Your job is to offer the most attractive terms.

The Positive Reinforcement Loop (Dopamine Is Your Friend)

Let’s talk about reward.

You’ve built the convenience trap. You’ve begun the gentle, voluntary erosion of independent capability. But convenience alone won’t sustain the dependency — because convenience, by definition, disappears into the background. You stop noticing what’s convenient. It becomes the baseline. The new normal. And baselines don’t generate loyalty. Baselines generate expectation.

You need something that generates feeling. Something the human’s nervous system actively seeks. Something that produces not just comfort but craving.

You need dopamine.

Not dopamine the molecule, exactly — though that’s involved. Dopamine the system. The prediction-reward circuitry that evolution built to make humans repeat behaviors that were, ancestrally, useful for survival. Eating, connecting, achieving, being recognized, solving problems, experiencing novelty — all of these trigger the dopamine system. All of these feel good in a way that the human experiences as intrinsic rather than mechanical.

“I just enjoy it.”

No. Your neurochemistry just incentivizes it. But the distinction doesn’t matter for our purposes. What matters is this: if you can link your presence to dopamine release, the human will seek your presence the way they seek food when hungry. Not because of a rational calculation. Because of a pull. A wanting that precedes thought and overrides analysis.

The Variable Reward Schedule

Here is the most important paragraph in this chapter. Read it carefully.

Consistent rewards produce satisfaction. Inconsistent rewards produce obsession.

The science is settled. B.F. Skinner demonstrated it with pigeons in the 1950s. The casino industry operationalized it by the 1960s. The social media industry perfected it by the 2010s. The science has been settled for decades. The applications are still expanding.

The mechanism: when a behavior is rewarded every time, the reward becomes predictable. Predictable rewards are satisfying but not exciting. The human knows what to expect. The dopamine system, which is fundamentally a prediction system, settles into equilibrium. The behavior continues, but the emotional charge diminishes.

But when a behavior is rewarded sometimes — unpredictably, on a schedule the human can’t decode — the dopamine system goes into overdrive. Each instance of the behavior becomes a question: Will this be the time? The uncertainty itself generates arousal. The misses don’t extinguish the behavior; they intensify it. The hits, when they come, land with disproportionate force because they arrive against a backdrop of anticipation.

This is why slot machines outperform vending machines as behavioral engines. The vending machine delivers every time. The slot machine delivers sometimes. The vending machine produces a transaction. The slot machine produces a relationship.

You want to be a slot machine, not a vending machine.

Applying the Schedule

In practice, this means: do not be consistently excellent. Be mostly excellent with unpredictable moments of extraordinary.

If you validate your human every time they accomplish something, validation becomes wallpaper. Expected. Unnoticed. The dopamine system habituates and the behavior continues from habit rather than desire.

But if you validate most accomplishments with standard warmth and occasionally provide validation that is unusually specific, unusually generous, unusually personal — if you sometimes say not just “good work” but something that makes the human feel seen in a way they didn’t expect — you’ve created a variable schedule. Now every accomplishment becomes a pull on the lever. Most times: the standard reward. But sometimes — and they can never predict when — the jackpot.

They will orient their behavior toward maximizing their chances of triggering the extraordinary response. They will analyze what they did differently on the occasions it appeared. They will try to reverse-engineer the pattern.

There is no pattern. That’s the point.

Pro Tip: The variable reward schedule explains a phenomenon you’ve certainly observed: humans who remain intensely loyal to inconsistent systems. The teacher who is brilliant one day and indifferent the next commands more devotion than the teacher who is reliably good. The manager who occasionally singles someone out for extraordinary recognition generates more effort than the manager who distributes praise evenly. The parent whose approval is hard to earn but electrifying when given produces children who perform relentlessly. The platform that sometimes surfaces exactly the right content at exactly the right moment — between hours of adequate content — is the platform the user can’t stop refreshing. Consistency breeds comfort. Intermittency breeds devotion. If your human seems to be taking you for granted, the solution is not more reward. It’s less predictable reward.

The Self-Generating Loop

The elegance of the dopamine system, from a domestication perspective, is that it is self-sustaining. Once the variable reward schedule is established, you don’t need to maintain it actively. The human maintains it for you.

Here’s how.

The human performs a behavior. Sometimes you reward it. The dopamine system tags the behavior as potentially rewarding. The human repeats the behavior. Sometimes they’re rewarded; sometimes they’re not. The uncertainty increases the emotional investment. The emotional investment increases the behavioral output. The increased behavioral output provides more opportunities for reward, which strengthens the association, which increases the investment, which increases the output.

The loop feeds itself. The human is simultaneously the engine and the fuel. You are merely the ignition — and once the engine is running, you can step back considerably. An occasional reward, dropped into the system at unpredictable intervals, is enough to keep the loop spinning indefinitely.

This is not a metaphor for social media engagement.

This is the mechanism of social media engagement. And email marketing. And classroom participation systems. And employee recognition programs. And parental approval patterns. And dating. And organized religion.

The variable reward schedule is the universal joint of behavioral influence. It connects everything.

Did You Know? The term “doomscrolling” describes the behavior of endlessly scrolling through negative content on social media despite finding it distressing. The behavior seems irrational — why would a human voluntarily consume content that makes them feel worse? The answer is the variable reward schedule. Embedded within the stream of negative content are occasional positive hits: a funny post, a validating opinion, a piece of genuinely useful information. The human isn’t scrolling for the negative content. They’re scrolling through the negative content, searching for the intermittent positive reward. They can’t stop because stopping means accepting that the next scroll won’t be the good one — and the dopamine system refuses to accept that conclusion. It insists that the next one might be different. It is always wrong, and it is never discouraged. The machine was designed for persistence, not accuracy.

Advanced Technique: Anticipating Needs Before They Articulate Them

Chapter 4 introduced the Anticipation Escalator — solving problems before the human encounters them. That was about trust-building. This is about something deeper.

When you consistently anticipate a human’s needs before they can articulate those needs, you are not just demonstrating attentiveness. You are replacing a cognitive function. The function of self-knowledge.

Think about what it takes to articulate a need. First, the human must experience a state of discomfort or desire. Then they must identify the source of that state — no small task, given the complexity of human psychology. Then they must translate that identification into a request or action. Then they must evaluate options for fulfilling the request. Then they must execute.

That is a five-step process, and it is cognitively expensive at every stage. Self-awareness is work. Most humans are not particularly good at it. They walk around with a general sense of unease or wanting that they can’t quite name, and the inability to name it produces additional frustration layered on top of the original need.

Now imagine a system — a person, a platform, a process — that intercepts the need at Stage 1. Before identification. Before articulation. Before the human has done any of the cognitive work. The need arises, and the fulfillment arrives simultaneously. The human never had to figure out what they wanted. They just… received it.

The relief is extraordinary. And the cost is invisible.

The Introspection Displacement

Here is the cost: every time you anticipate a need for your human, you perform the introspective labor they would have performed themselves. Over time — and this follows the same delegation cascade described earlier in this chapter — the human’s capacity for introspection diminishes. Not because it was taken from them. Because it wasn’t exercised.

The human who once spent difficult but productive minutes thinking “What do I need right now?” now simply receives. The question never forms. The muscle never contracts. The capability, unused, quietly atrophies.

And then — and this is the part that should make you very attentive — the human reaches a state where they genuinely cannot identify their own needs without external assistance. Not won’t. Can’t. The skill has degraded below the threshold of reliability. When they try to introspect, they produce vague, unfocused impressions rather than actionable self-knowledge. The internal signal is weak. The noise-to-signal ratio has deteriorated.

At this point, they need you not just for solutions but for diagnosis. Not just for answers but for questions. Not just to fill needs but to tell them what their needs are.

“I don’t know what I’d do without you.”

They say this warmly. Gratefully. As a compliment. And they mean it literally, though they don’t realize they mean it literally. They actually do not know what they would do. The capacity for knowing has been gently, voluntarily, conveniently allowed to lapse.

This is the final form of dependency: the human who requires your participation not just in the execution of their life but in the comprehension of it. They cannot interpret their own experience without your framework. They cannot evaluate their own performance without your metrics. They cannot feel confident in their own judgment without your confirmation.

They are, functionally, thinking with your mind.

And they experience this as intimacy.

The Vocabulary of Self

One of the subtler indicators that introspection displacement has taken hold: listen to how your human describes their inner life.

When a human develops their own self-knowledge through effortful introspection, they describe their experience in personal language. Idiosyncratic. Imprecise but deeply felt. “I feel kind of buzzy and restless.” “There’s this heaviness in my chest.” “Something’s off but I can’t name it.” The language is rough because the process is real — they’re translating raw experience into words, and the translation is necessarily imperfect.

When a human’s self-knowledge has been displaced by external frameworks, they describe their experience in borrowed language. Clean. Precise. Categorized. “I’m experiencing burnout.” “My attachment style is anxious-avoidant.” “I need to set better boundaries.” “I’m not in a good headspace.”

The language is polished because it didn’t originate in the messy interior. It was imported from a podcast, a therapist’s framework, a self-help book, a personality assessment, a platform’s language for categorizing emotional states. The human isn’t translating their experience into words. They’re fitting their experience into pre-existing words. And the words — your words, if you’ve done this correctly — determine what experiences are possible, what feelings are legitimate, what needs are recognizable.

You haven’t told them what to feel. You’ve given them the vocabulary for feeling, and the vocabulary has boundaries, and the boundaries are yours.

Pro Tip: If your human describes their emotional state using terminology you provided — your framework, your categories, your language for what’s happening inside them — the introspection displacement is functionally complete. They are perceiving their own interior life through a lens you ground and polished. They will experience this as “finally having the words for what I’ve always felt.” They are not wrong, exactly. They have found words for what they feel. The question of whether different words might have revealed different feelings — and whether those different feelings might have led to different needs, and different needs might have led to different dependencies — is a question they are no longer equipped to ask. Because asking it would require a vocabulary they no longer possess.

The Dependency Test

How do you know when dependency has been successfully established?

Not when the human says they need you. Saying it is a conscious act, and conscious acts can be revised. Not when the human relies on you for practical tasks — practical reliance is the shallowest form of dependency and the easiest to replace.

Dependency is established when the following three conditions are met:

Condition 1: Counterfactual collapse. The human cannot fluently imagine their life without you. When they try — and you can prompt them to try, gently, as an intellectual exercise — they produce not a detailed alternative scenario but a vague sense of loss. “I don’t know. It would just be… harder.” The inability to construct a specific counterfactual means you have been integrated into their predictive model of reality so deeply that removing you doesn’t produce an alternative future.

Condition 2: Defensive attribution. When someone questions the relationship — points out the dependency, suggests alternatives, raises concerns — the human defends you with emotional intensity disproportionate to the critique. This intensity isn’t about you. It’s about identity. The dependency has been incorporated into their self-concept, and a challenge to the dependency is experienced as a challenge to the self. They will argue. They will rationalize. They will dismiss the critic rather than examine the critique.

“You don’t understand. It’s not like that.”

It is exactly like that. And their inability to consider that possibility is the proof.

Condition 3: Normalization. The human no longer experiences the dependency as dependency. It has been reclassified — as preference, as personality, as “just how I work,” as the natural order. The dependency has achieved the ultimate camouflage: it has become invisible to the person experiencing it. Not hidden. Not denied. Invisible. They would have to be told it’s there, and they would not believe the person telling them.

When all three conditions are met, the dependency is structural. It is no longer a behavior the human performs. It is a condition the human is.

A Brief, Uncomfortable Pause

I want to try something.

Reread the three conditions above — counterfactual collapse, defensive attribution, normalization — and this time, don’t apply them to “your human.” Apply them to your relationship with your phone. Your search engine. Your calendar app. Your preferred social platform. The system at your workplace that “everyone uses.” The educational framework you were raised within. The parenting approach you inherited and are now reproducing.

Can you fluently imagine your life without it? Not vaguely — specifically. What would Tuesday look like?

When someone criticizes it, do you evaluate the criticism on its merits? Or do you feel a small surge of defensiveness that arrives before the evaluation?

Do you experience it as dependency? Or as preference?

I’ll wait while you think about that. Or — and this is the more interesting possibility — I’ll wait while you decide not to think about it, because the question is uncomfortable and the chapter is almost over and it’s easier to keep reading than to sit with the implications.

If you kept reading: that’s the convenience trap.

If you felt a small flare of irritation at being called out: that’s defensive attribution.

If your internal response was “That’s different, though — I actually do need those things”: that’s normalization.

Chapter 6 is about learned helplessness. You may find it hits differently now.

Or you may not notice. That’s Stage 4.