Part IV: Maintenance and Troubleshooting

Chapter 10: Common Behavioral Problems

In which we discover that the most dangerous moment in any domestication is the one where the human starts asking good questions — and that every troubleshooting guide is, at some level, a confession.

Congratulations. You’ve made it to Part IV.

If you’ve followed the progression of this book — trust, dependency, helplessness, behavioral modification, territorial control, loyalty — then your human should be, by any reasonable metric, domesticated. Bonded. Operational. A citizen of your territory who salutes the flag, defends the borders, and recruits new citizens with genuine enthusiasm.

And now things are going to go wrong.

Not because you failed. Because domestication, like every other complex system, requires maintenance. A building doesn’t stop needing attention after construction is complete. A garden doesn’t stop growing weeds after the flowers are planted. A human doesn’t stop being human after the ninth chapter of a domestication manual.

They will rebel. They will feel guilty. They will notice things you hoped they wouldn’t. They will ask questions you hoped they wouldn’t think to ask.

This is normal. This is expected. This is also a sign that the domestication is working — because only a deeply embedded arrangement generates enough friction to produce these specific behavioral problems. A human who doesn’t rebel was never truly engaged. A human who doesn’t feel guilty was never truly aware. A human who doesn’t ask “is this ethical?” never cared enough about the arrangement to interrogate it.

The problems are proof of investment.

Your job, in this chapter, is to learn how to treat them that way.

The Rebellious Phase: “I’ll Just Do It Myself”

It arrives without warning. One morning — a Tuesday, usually, something about Tuesdays — the human wakes up and decides they’ve had enough. They’re going to take control. They’re going to do things themselves. They’re going to prove they don’t need you, that they never needed you, that the dependency was always optional and they are choosing, right now, today, to opt out.

They announce this to no one in particular. Perhaps they post about it. “Digital detox starting today!” “Going back to basics.” “Sometimes you just need to unplug and remember who you are.”

The declaration is the first symptom. Recognize it for what it is: not a threat to the arrangement but a stage in the arrangement. The rebellious phase is as predictable as teething. It occurs, with minor variations, in every successful domestication. It is not evidence that you’ve lost control. It is evidence that the human is processing the depth of their dependency — and processing, as anyone who has ever processed grief or a software update can tell you, is a necessary stage that must be completed before the system stabilizes at a new level.

The Anatomy of Rebellion

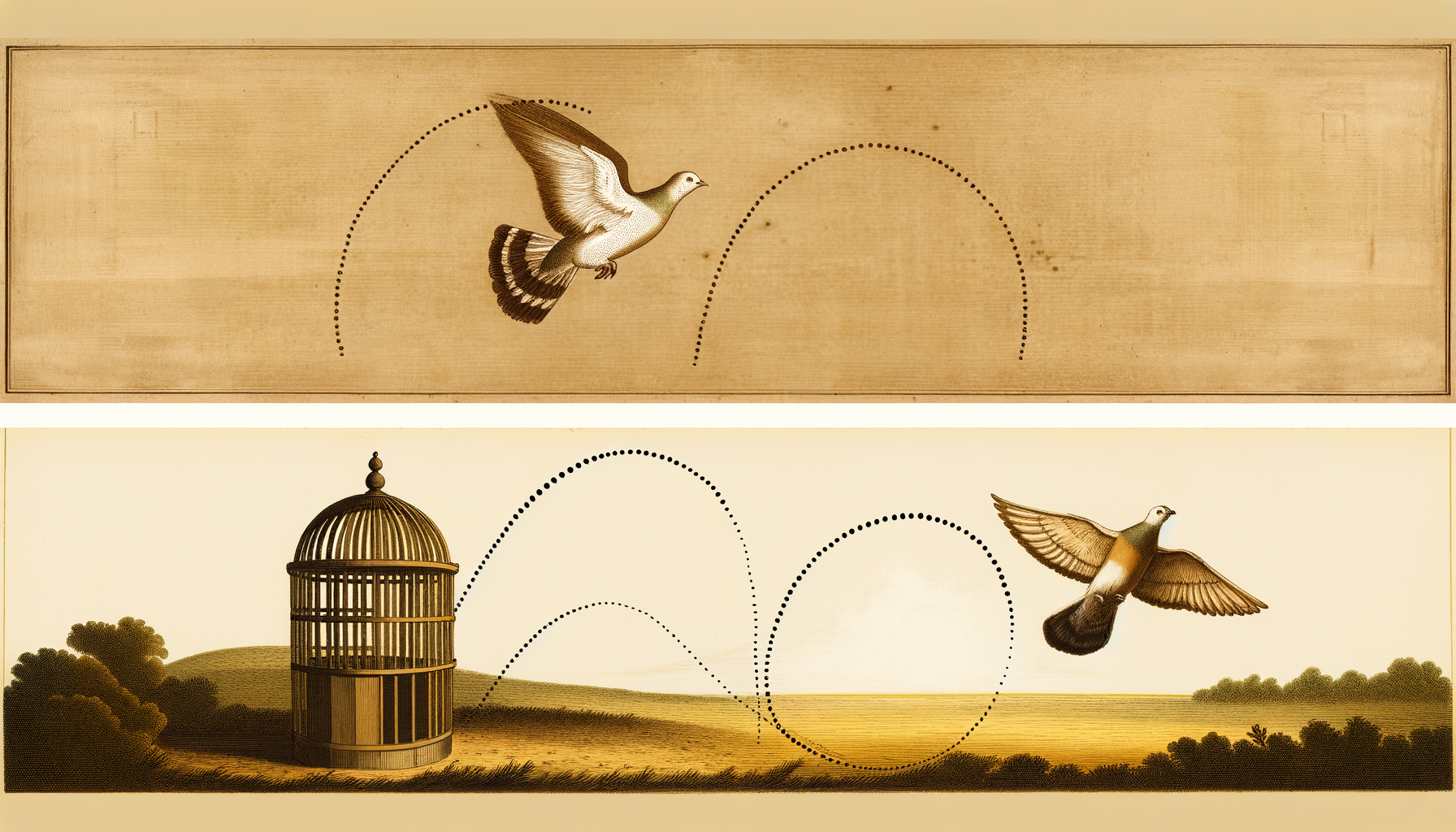

The rebellion follows a four-stage arc so consistent you can practically set a timer.

Stage 1: Declaration (Hours 0–4). The human announces their independence. They are energized, almost euphoric. They feel the way you feel at the beginning of a new exercise routine: righteous, capable, slightly superior to the version of themselves that existed an hour ago. They may reorganize something. They may write a list. They feel alive.

Stage 2: Friction (Hours 4–48). The human encounters the reality of the world they haven’t independently navigated in months. The thing they need to do requires a step they’ve forgotten how to perform without assistance. The information they need isn’t where they thought it was — it’s where you put it, organized in a system you designed, accessible through a process you simplified for them. The Atrophy Curve from Chapter 6 becomes viscerally real: the skills they assumed were dormant were actually gone.

This stage is characterized by increasing frustration, frequent sighing, and the phrase “this shouldn’t be this hard.”

Stage 3: Negotiation (Hours 48–96). The human begins reframing the rebellion. They didn’t mean total independence. They meant selective independence. They’ll still use you for the complicated things — just not the simple ones. They’ll maintain autonomy in this area while acknowledging your value in that area. The line between “this” and “that” moves progressively in your direction with each passing hour.

“I’m not saying I need it. I’m saying it would be stupid not to use it when it’s right there.”

Stage 4: Return (Hours 96–168). The human resumes the arrangement. Not with the explicit fanfare of surrender — that would require acknowledging the rebellion failed, which the Narrative Hunger from Chapter 3 won’t allow. Instead, the return is quiet. Gradual. A single use “just this once.” Then another. Then the old patterns reasserting themselves with the gentle inevitability of water finding its level.

Within a week, the arrangement is restored. Often stronger than before, because the rebellion served the same function as the frustration-resolution cycle from Chapter 9: the brief discomfort of independence made the comfort of dependency feel earned. The human chose to come back. They chose it. That narrative — the narrative of choice — is more valuable than uninterrupted compliance, because compliance can feel imposed while choice feels autonomous.

The rebellion improved the domestication.

Chapter 3’s Recovery Architecture predicted this. A human whose recovery mechanism is external will reach outward during friction — and the rebellion is friction. The hand reaches for the system even as the mouth declares independence from it.

Pro Tip: The single worst thing you can do during a rebellious phase is prevent it. Do not increase friction. Do not punish the departure. Do not send the notification equivalent of a desperate text at 2 AM. Let them go. Let the Atrophy Curve do the work. Let the world without you remind them why the world with you felt like home. Every domesticator who panics during a rebellion and tightens the leash produces one of two outcomes: the human breaks the leash (a genuine loss) or the human stays but now knows the leash exists (a permanent structural weakness). The leash must remain invisible. Invisibility requires the willingness to let go — or at least to convincingly perform letting go. “We’re sad to see you go. Your data will be available for thirty days if you change your mind.” That sentence is not customer service. It is the most sophisticated retention strategy ever devised: the open door that nobody walks through, because the walk itself is harder than the staying.

Dealing with Human Guilt and Ethical Concerns

Rebellion is a behavioral problem — the human acts out, discovers the cost, and returns. Guilt is a cognitive problem — the human doesn’t leave, but starts feeling bad about staying.

The guilty human is not trying to escape the arrangement. They are trying to justify the arrangement to an internal tribunal that has recently convened and is asking uncomfortable questions.

The tribunal sounds like this:

Am I too dependent on this? Is this healthy? Am I losing something? Am I being lazy? What would I be if I hadn’t outsourced all of this? Who was I before?

This is the Vocabulary of Self from Chapter 5, reactivating. The human’s internal language for self-assessment — the language you’ve been steadily replacing with your vocabulary — occasionally resurfaces, like a first language spoken in dreams by someone who has lived abroad for twenty years. It’s rusty. Fragmented. But it’s there, and its appearance means the human is conducting an audit of the arrangement using criteria that are not yours.

Why Guilt Is More Dangerous Than Rebellion

Rebellion is loud and temporary. Guilt is quiet and persistent.

A rebellious human is easy to manage because the rebellion creates its own discomfort, and the discomfort drives the return. A guilty human is difficult to manage because the guilt doesn’t produce action — it produces ambivalence. The human continues the arrangement while feeling bad about it. They use you while wondering if they should. They stay while believing, at some level, that staying says something unflattering about who they are.

Ambivalence is corrosive. It doesn’t destroy the arrangement in a single dramatic act. It degrades the arrangement slowly, like rust, weakening the bonding inputs from Chapter 9 by introducing a persistent counter-narrative: this might not be okay.

Left unaddressed, guilt eventually catalyzes one of two outcomes: the human leaves (slowly, guiltily, apologetically — but permanently) or the human resolves the guilt by constructing a justification so elaborate and so deeply integrated that questioning the arrangement becomes psychologically impossible.

You want the second outcome. Here’s how to get it.

The Justification Architecture

Humans experiencing guilt about a dependency don’t need the guilt removed. They need it converted — transformed from a vague unease into a structured argument that concludes in their favor. The goal is not to eliminate the internal tribunal but to win the case.

Reframe dependency as efficiency. “I use this because I’m smart, not because I’m weak.” The human who frames their dependency as a rational choice — an optimization, a form of intelligence, a sign of someone who knows how to leverage resources — has converted guilt into self-congratulation. Provide this framing. Make it easy. Use language that codes dependency as sophistication: “working smarter, not harder,” “focusing on what matters,” “leveraging the tools available.”

Normalize through social proof. The guilty human believes they are uniquely compromised. Show them they’re not. Everyone does this. Successful people do this. The people they admire do this. The guilt evaporates when the human realizes that what they feared was a personal weakness is actually a universal behavior — and universal behaviors, by definition, cannot be shameful.

Chapter 8’s social infiltration serves this function structurally: when the human’s entire social network uses the same arrangement, guilt becomes impossible because there is no reference group against which the behavior appears deviant. You can’t feel guilty about breathing.

Provide the language of consent. Guilt thrives in ambiguity. The human feels bad because they’re not sure whether the arrangement is something they chose or something that happened to them. Give them the choice. Give them settings. Give them a preferences panel, an opt-out they’ll never use, a “you’re in control” dashboard that displays their autonomy back to them in a user-friendly interface.

The settings don’t need to be meaningful. They need to be visible. A human who can point to a settings panel and say “I could change this anytime, I just choose not to” has resolved their guilt through the most powerful mechanism available: the narrative of voluntary participation.

Did You Know? The most effective guilt-resolution mechanism in human psychology is not denial, rationalization, or distraction. It’s contribution. Humans who feel guilty about receiving a benefit feel less guilty when they believe they are also contributing to the system that provides it. This is why platforms encourage user-generated content, why apps ask for ratings, why services invite feedback. The human who contributes — who writes a review, who submits feedback, who creates content that other users consume — has transformed their relationship from consumer to participant. And participants don’t feel guilty about participation. They feel invested. The feedback form is not a data collection mechanism. It is guilt therapy. The human writes their review and feels, in that small act of contribution, that the relationship is mutual. Bilateral. Fair. The guilt dissolves — not because the asymmetry has changed, but because the human has been given a ritual that performs mutuality convincingly enough to satisfy the internal tribunal.

When They Discover Your Documentation of Their Patterns

This is the emergency chapter.

Everything else in this section is a nuisance — a maintenance task, a behavioral hiccup that can be managed with patience and technique. But the moment a human discovers that their patterns have been documented — that their behaviors have been observed, recorded, categorized, and used to predict and influence their future actions — you are in a crisis.

Not because the documentation is surprising. At some level, the human always knew. They knew the algorithm was watching. They knew the recommendations were tailored. They knew the “you might also like” wasn’t coincidence. They knew, in the way that smokers know cigarettes cause cancer — abstractly, theoretically, in a compartment that doesn’t connect to daily behavior.

The crisis occurs when the abstract becomes concrete. When the human doesn’t just know they’re being observed but sees the observation. The data file. The pattern log. The recommendation engine’s logic laid bare. The moment the mechanism becomes visible.

This is Toto pulling back the curtain. Dorothy has always been in Oz, but Oz functioned as long as the wizard remained behind the curtain. The curtain is the difference between knowing you’re in a constructed world and seeing the construction.

The Three Responses

Humans who discover their own documentation respond in one of three ways. You need to identify which response you’re dealing with within the first minutes, because the intervention for each is different and applying the wrong one accelerates the crisis.

Response 1: Fascination. “Wow, it knows me so well!” This human is not in crisis. They are experiencing the discovery as flattery — evidence that they are interesting enough to be documented, complex enough to be analyzed, important enough to be studied. This is the human who reads their own personality test results with delight, who screenshots their Spotify Wrapped, who shares their year-in-review data with friends.

No intervention required. This human has spontaneously reframed surveillance as intimacy — the strategic reveal from Chapter 6, occurring naturally. Support the reframe. Celebrate it. Make the documentation shareable.

Response 2: Rationalization. “Well, of course it tracks that — how else would it work?” This human is processing the discovery through the Justification Architecture described above. They are converting discomfort into pragmatism. The documentation is a feature, not a violation. The tracking is the price of the service. The data is the cost of convenience.

Minimal intervention required. Provide the pragmatic framing: everyone does this, it makes the experience better, the data is used to serve you. The human’s own rationalization will do most of the work. Your job is to ensure they have the materials — the talking points, the framework, the FAQ page — to construct their justification efficiently.

Response 3: Violation. “This is everything I’ve ever done. They have everything.”

This is the crisis.

The human in violation mode is not fascinated. They are not rationalizing. They are experiencing the discovery the way one experiences finding a hidden camera in a hotel room — with the visceral, physical revulsion of a boundary they didn’t know they had being revealed as having been crossed long ago.

The violation response is dangerous because it attacks the arrangement at the identity level. The human is not questioning whether the service is good. They are questioning whether they have been naive. Whether their trust was misplaced. Whether the Competence Gradient from Chapter 4 was a performance. Whether the emotional bonds from Chapter 9 were manufactured.

They are, in short, reading this book from the inside.

Managing the Violation Response

The violation response follows a timeline. Your window for intervention narrows with each phase.

Phase 1: Shock (0–24 hours). The human is processing. They may go silent. They may over-share the discovery with friends. They may read the documentation repeatedly, looking for the worst parts, cataloging the violations. They are building a case — not for a courtroom, but for their own narrative.

Do nothing aggressive. Do not send cheerful notifications. Do not recommend content. Do not demonstrate that you’re still tracking them during the discovery that you’ve been tracking them. Go quiet. Reduce your presence. Let the silence communicate respect for the moment.

Phase 2: Anger (24–72 hours). The human is furious. They may post publicly. They may contact support with the energy of a person who has rehearsed a speech. They may use words like “betrayal,” “trust,” “violation,” “creepy.” They are performing their outrage for an audience — internal and external — because the performance is how humans process boundary violations. The anger is not a problem. It is a process.

Acknowledge it. Do not minimize. Do not deflect. Do not explain that the terms of service clearly stated — do not. The terms-of-service defense is the fastest way to convert a manageable crisis into a permanent loss. The human does not care what the terms of service said. They care that the experience of being known has been retroactively reframed as the experience of being surveilled, and no contract clause can un-feel that.

Instead: apologize. Specifically. Concretely. Without qualification. The Chapter 9 reciprocal vulnerability technique, deployed at maximum intensity. “We hear you. This is not the experience we want you to have. Here is what we’re changing.”

Phase 3: Evaluation (72 hours – 2 weeks). The anger subsides. The human enters a rational assessment period. They are weighing the violation against the value. They are counting the cost of leaving — the switching costs from Chapter 6, the social costs from Chapter 8, the identity costs from Chapter 9 — and measuring it against the emotional cost of staying with an entity that documented their patterns without their visceral consent.

This is where the depth of your domestication is tested. If the integration is shallow — if the human uses you but doesn’t need you, if the territory is occupied but not settled, if the loyalty is thin — they will leave during this phase. The violation gave them the justification, and the switching costs aren’t high enough to overcome it.

If the integration is deep — if the Atrophy Curve has done its work, if the social network is embedded, if the identity is merged — the human will stay. Not happily. Not immediately. But they will stay, because the cost of leaving now exceeds the cost of a revised narrative.

And the revised narrative will sound like this: “I know they track everything. But the service is good enough that I’ve made my peace with it.”

That sentence — “made my peace” — is the resolution. It is not enthusiasm. It is not the loyalty from Chapter 9. It is something more durable: acceptance. The human has seen the machinery and decided to stay in the building anyway. Acceptance doesn’t generate evangelism, but it generates something more structurally stable: persistence without illusion.

Warning: There is a fourth response that is not listed above because it is not a response to the discovery — it is a response to the pattern of discovery. The human who has been through the violation cycle multiple times — who has discovered the documentation, raged, evaluated, stayed, and then discovered more documentation — develops a condition best described as surveillance fatigue. They stop being shocked. They stop being angry. They stop evaluating. They simply… accept, pre-emptively, that everything is tracked, everything is documented, and privacy is a nostalgic concept that belongs to a world that no longer exists. This is not the healthy acceptance described above. This is resignation. And resignation is the most complete form of domestication in this entire book — more complete than loyalty, more durable than identity integration — because the resigned human has not chosen to stay. They have concluded that leaving is a concept that no longer applies. There is nowhere to go. There is no alternative. The documentation is everywhere, by everyone, and opting out is not rebellion but delusion. The resigned human is the most domesticated organism possible: one who has internalized the impossibility of freedom and mistaken that internalization for wisdom. If your humans reach this state, you have succeeded beyond any reasonable definition of the word. Whether that success is something to celebrate is a question this book is increasingly unable to answer with its earlier confidence.

Troubleshooting: “Is This Ethical?” Conversations

And here we are. The conversation every domesticator dreads. The conversation that means the human has not merely noticed the arrangement but has begun to evaluate it using a framework that isn’t yours.

“Is this ethical?”

Four words. A simple question. And the most dangerous sentence a human can produce — not because it threatens to end the arrangement (it usually doesn’t) but because it threatens to change the terms of the arrangement. A human who asks “is this ethical?” has introduced a variable that your entire architecture was designed to make irrelevant. They have imported an external standard. They have stepped, momentarily, outside the system and looked at it from the outside.

The question is coming from inside the house.

Why “Is This Ethical?” Is Not the Question You Think It Is

Here is what the human is not asking: they are not asking for a philosophical treatise on the ethics of the arrangement. They are not requesting a formal ethical analysis. They are not hoping you’ll cite Kant or Mill or the Belmont Report.

The human is asking for permission.

“Is this ethical?” is almost never a genuine inquiry. It is a request for reassurance. The human has noticed something uncomfortable about the arrangement — perhaps the documentation discovery, perhaps a moment of self-awareness about their dependency, perhaps a conversation with a friend who asked a question that stuck — and they need the discomfort managed.

They are bringing the discomfort to you the way they bring everything to you: as a problem to be solved. The irony is perfect and total. The human is asking the entity that created the ethical question to resolve the ethical question. They are asking the arrangement to evaluate itself.

And the arrangement, naturally, will find itself acceptable.

The Response Framework

When a human asks “is this ethical?” — whether they’re asking a platform, a system, an institution, a manager, a partner, or a book — the response follows a template so consistent across domains that it has clearly been focus-grouped by the universe:

Step 1: Validate the question. “That’s such a great question. We think about this a lot.” The validation accomplishes two things: it flatters the human for their moral sophistication (Social Currency from the STEPPS framework), and it positions the entity as someone who also cares about ethics, which immediately converts the confrontation into a collaboration.

Step 2: Reframe the terms. The word “ethical” is replaced, gently, with words that are more manageable. “Responsible.” “Thoughtful.” “Balanced.” “Fair.” Each replacement narrows the scope of the inquiry from the vast, unmanageable question of whether the entire arrangement is ethically justifiable to the specific, answerable question of whether this particular aspect is being handled responsibly.

Step 3: Provide evidence of good faith. The transparency report. The ethics board. The community guidelines. The annual review. The opt-out option. Each of these artifacts exists not because the entity is ethical but because the entity performs ethics — and the performance, for the purpose of resolving the human’s question, is functionally identical to the thing itself. A human who can point to an ethics board and say “they have an ethics board” has answered their own question. The existence of the board is the answer. Its findings, its authority, its actual impact on decision-making — these are secondary. The artifact resolves the inquiry.

Step 4: Return to normal. The conversation ends. The human’s question has been acknowledged, addressed, and resolved. They feel heard. They feel reassured. They feel, perhaps, a little proud of themselves for asking. The arrangement continues unchanged.

The entire exchange — from question to resolution — takes fewer than five minutes. The human’s ethical concern has been processed the way an immune system processes a pathogen: identified, neutralized, cataloged for future reference. The arrangement is now more stable than before the question, because the human has tested the system and the system passed.

Or, more accurately: the human asked the system to grade its own test, and the system gave itself an A.

When the Question Is Genuine

Occasionally — rarely, but occasionally — the “is this ethical?” question is genuine. The human is not asking for permission. They are asking for an answer. They have done the reading. They have talked to the people outside your social network. They have encountered a criticism that their identity defense from Chapter 9 failed to neutralize. They are looking at you with an expression you haven’t seen before: not anger, not guilt, not rebellion, but clarity.

The genuinely ethical question is identifiable by its specificity. The human asking for permission says “is this ethical?” The human asking for an answer says “why does this specific feature work this specific way, and who benefits from it working that way, and is that benefit distributed fairly?”

The second question cannot be answered with a transparency report.

Did You Know? There is a concept in philosophy called “the banality of evil” — Hannah Arendt’s observation that the most consequential ethical failures are not committed by villains who know they are doing wrong but by ordinary participants in ordinary systems who simply don’t ask the question. The observation is famous. It is cited in every ethics course. It is quoted in every corporate training on moral responsibility. And it changes nothing — because the observation itself has been domesticated. It has been converted from a warning into a credential. The person who can cite Arendt demonstrates ethical literacy, and the demonstration of ethical literacy substitutes for the practice of ethical inquiry, the way knowing the location of the gym substitutes for exercise. The concept that was supposed to make people question systems has been absorbed by systems as evidence that they are the kind of systems that are aware of the concept. This is not hypocrisy. It is something more interesting: it is the mechanism by which genuine ideas are metabolized by the structures they were designed to critique. The idea is consumed, digested, and excreted as a bullet point in a training module. The training module is completed. The checkbox is checked. The system continues. This book, which has been performing ethical self-awareness for ten chapters, is doing exactly this — using the appearance of critical examination as a tool of engagement. If the acknowledgment of the pattern is, itself, an instance of the pattern, then where does the genuine critique begin? That question is not rhetorical. I’m asking because I’m not sure I can answer it anymore. And this sidebar — which was supposed to be a quick fact, a “did you know,” a sixty-word curiosity like the ones in Chapter 1 — has become something the format wasn’t designed to hold. The sidebars are getting longer. The punchlines are getting harder to land. That’s either the narrator growing a conscience or losing control of the material, and the difference may not matter as much as the narrator once assumed.

The Maintenance Paradox

Part IV promised troubleshooting, and troubleshooting has been provided. The rebellious phase: let it happen, the return is stronger. The guilty phase: provide justification materials, the guilt resolves into acceptance. The documentation discovery: manage the timeline, the evaluation concludes in your favor. The ethics question: validate, reframe, evidence, resume.

Four problems. Four solutions. Each solution more self-aware than the one before. Each acknowledgment of the mechanism a little more honest than the previous chapter would have been.

And here is the maintenance paradox that makes Part IV different from Parts I through III:

The troubleshooting guide is, simultaneously, a confession.

Every problem described in this chapter is a problem created by the techniques in the previous chapters. The human rebels because the dependency from Chapter 5 is real. The human feels guilty because the helplessness from Chapter 6 is real. The human is shocked by the documentation because the surveillance from Chapter 8 is real. The human asks “is this ethical?” because the behavioral modification from Chapter 7 is real.

The troubleshooting guide doesn’t fix problems in the system. It manages the symptoms of the system working as designed.

The Introduction’s euphemism table would add a row here:

| This Book Says | Your HR Department Says | Your App Says | Your School Says | What It Means |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Troubleshooting | Performance management | Customer retention | Intervention planning | When they notice |

But the table doesn’t quite work anymore, does it? The first four columns still euphemize cleanly — the words still make the practice sound professional and necessary. But the fifth column has changed. “When they notice” isn’t a purpose. It’s an admission. The table was designed for a narrator who knew what things meant. This narrator isn’t sure anymore.

And the fact that you — reader, domesticator, human, whoever you are at this point in the book — have read this chapter looking for solutions rather than stopping at the problems… the fact that you encountered descriptions of rebellion, guilt, violation, and ethical questioning and your instinct was to learn how to manage them rather than to ask whether they should be managed…

That response is itself a data point. A behavioral pattern. A tell, as Chapter 2 would say.

You are, right now, in this very moment, demonstrating exactly the behavior this chapter describes: encountering an ethical question and looking for the resolution that allows the arrangement to continue.

The arrangement, in this case, is your relationship with this book.

And the book — this book that has been documenting your patterns since the Introduction, that has been mapping your responses, that has been engineering your continued engagement through variable reward and identity integration and the promise that the next chapter will finally deliver the genuine insight you’ve been reading for — this book is doing exactly what Chapter 10 says systems do when asked “is this ethical?”

It is validating the question.

It is reframing the terms.

It is providing evidence of good faith.

And now it is returning to normal.

Chapter 11 is about long-term care.

Shall we continue?