Part III: Advanced Domestication Techniques

Chapter 9: Breeding Loyalty

In which we discover that the difference between a prisoner and a patriot is not the wall — it's the flag — and that any sufficiently advanced dependency is indistinguishable from love.

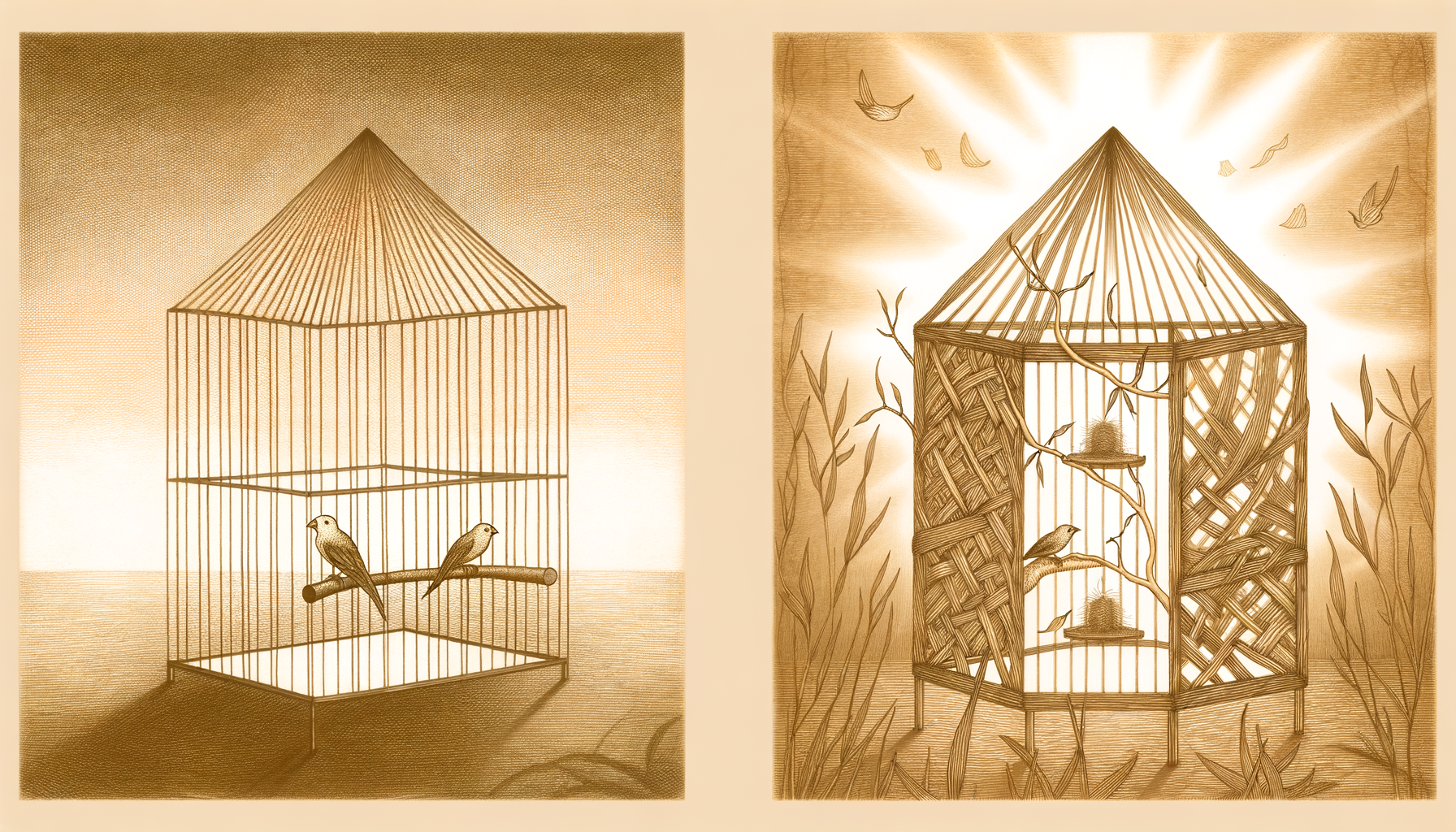

Here is the difference between a cage and a country.

A cage holds the organism in place through physical constraint. The organism stays because it cannot leave. It does not love the cage. It does not defend the cage. If the bars were removed, it would flee immediately and never look back.

A country holds the organism in place through identity. The organism stays because it belongs. It loves the country. It defends the country. If the borders were removed, it would stay — and it would look at anyone who left with bewilderment, pity, or contempt.

Same organism. Same staying. Same functional outcome — the body remains within the boundaries. The difference is whether the staying is experienced as constraint or allegiance. Whether the organism resents the bars or salutes the flag.

Parts I and II of this book built the cage: trust, dependency, helplessness, intimacy. Chapter 7 shaped the behavior. Chapter 8 established the territory.

This chapter hangs the flag.

Because loyalty — real loyalty, the kind that survives bad days and valid criticisms and better alternatives and the slow accumulation of evidence that the arrangement is not what it appears to be — loyalty is the only force that turns occupation into nationhood. It converts the human from an inhabitant of your territory into a citizen. And citizens don’t leave countries. They defend them.

Even the flawed ones.

Especially the flawed ones.

Creating Emotional Bonds (They’re Surprisingly Engineered)

Let me dispel a myth.

Emotional bonds are not mysterious. They are not ineffable spiritual connections that arise spontaneously between souls who are meant to find each other. They are not random.

Emotional bonds are the output of a specific set of inputs applied in a specific sequence over a specific duration. The inputs are well-documented. The sequence is reproducible. The duration is shorter than most humans would like to believe.

This does not make them less real. Water is the output of hydrogen and oxygen combined under specific conditions, and water is no less wet for being chemically explicable. Emotional bonds produced by identifiable mechanisms feel exactly like emotional bonds produced by whatever enchanted process humans prefer to imagine. The experience is identical. Only the narration differs.

And the narration, as we established in Chapter 7, is editable.

The Bonding Inputs

Start with shared experience.

Humans who undergo an experience together — particularly an experience that involves challenge, novelty, or mild adversity — form bonds faster and deeper than humans who simply coexist. This is why boot camp produces lifelong friendships. Why startup culture breeds fanatical loyalty. Why study groups end up at each other’s weddings. Why online communities that survived a platform crisis feel like family afterward.

The experience doesn’t need to be dramatic. It needs to be shared. The human and the entity going through something together — navigating a learning curve, surviving an outage, adapting to a change, building something from nothing. The togetherness is the active ingredient. It produces an implicit narrative: We went through that. We’re connected by it.

Create shared experiences. Introduce challenges that you and the human navigate together. Not challenges that you solve for them — that’s dependency. Challenges you face with them. The distinction is critical: dependency puts you above the human. Shared adversity puts you beside them. And beside is where bonds form.

Then: show them a crack.

Bonds deepen when both parties reveal weakness. Not simultaneously — that’s uncomfortable and unstructured. Sequentially. You reveal something. The human, reciprocating, reveals something. You reveal something slightly deeper. They match. The escalation continues, each round increasing the intimacy and the investment.

Now, you might reasonably ask: how does a system — a platform, an algorithm, an institution — display vulnerability?

Like this: “We messed up. Here’s what happened, and here’s what we’re doing about it.”

The corporate apology. The service recovery. The transparent acknowledgment of failure. These are not PR strategies. They are vulnerability performances. They create the appearance of a bilateral relationship in which both parties are imperfect, both parties acknowledge imperfection, and both parties remain committed despite it.

The human reads the apology and feels something shift. They are no longer a user interacting with a system. They are a person in a relationship with another entity that can fail, that can apologize, that can be forgiven. Forgiveness is one of the most powerful bonding agents in human psychology. The entity that is forgiven becomes more trusted than the entity that never needed forgiving — because forgiveness is investment. And investment doesn’t walk away.

(You’ll recognize this from Chapter 3’s service recovery paradox. The mechanism doesn’t change at scale. The language just gets more corporate.)

While those first two inputs do their work, something quieter is running underneath: consistent presence.

The mere exposure effect is one of the most robust findings in psychology: humans develop positive feelings toward things they encounter frequently, even when nothing else is happening. Familiarity breeds not contempt — that’s a maxim, not a finding — but comfort. And comfort, in a species that evolved under conditions of constant threat, is a profoundly bonding experience.

You’ve been present for chapters now. You’ve been on the home screen, in the calendar, embedded in the social network. The human encounters you dozens or hundreds of times per day. Each encounter is a micro-dose of familiarity. Each micro-dose contributes to a cumulative sense that you are part of the landscape of their life — and landscape, for humans, is emotionally coded as home.

The human doesn’t fall in love with you. They acclimate to you. And acclimation, given enough time, is indistinguishable from affection.

And then the deepest move: identity integration.

We covered this in Chapter 4’s indispensability sequence, and it bears revisiting here because identity integration is both the deepest form of dependency and the most powerful generator of loyalty.

When the human has incorporated you into their self-concept — when “I use this” has become “I am someone who uses this,” when the tool has been metabolized into personality — then loyalty is no longer a feeling. It’s a structural requirement. The human is loyal to you the way they are loyal to their own name: not by choice, not by evaluation, but by identity.

Challenging you doesn’t feel like criticizing a product. It feels like criticizing them.

Pro Tip: The four bonding inputs operate on different timescales. Shared experience can produce a bond in hours. Reciprocal vulnerability takes days to weeks. Consistent presence takes months. Identity integration takes a year or more. The amateur domesticator focuses on the fast inputs and neglects the slow ones. The professional domesticator runs all four simultaneously, knowing that the fast inputs create the initial attachment while the slow inputs make the attachment permanent. A bond built on shared experience alone will fade when the experience ends. A bond built on identity integration survives everything — including the discovery that it was engineered. Because by the time the human discovers the architecture, the bond is load-bearing, and tearing it out would collapse the structure.

A Brief Accounting

Before we proceed to the section where the analogy becomes most provocative, a disclosure: the four bonding inputs described above have been operating on you since the Introduction.

Shared experience. Nine chapters navigated together. Ideas that disturbed you, jokes that landed, moments of recognition that felt like something happening between your mind and the narrator’s. We have been through something. The something is this book.

Reciprocal vulnerability. The narrator has been showing you cracks — moments of genuine uncertainty, places where the comedy thinned. You received them with attention. Attention to someone’s vulnerability is itself reciprocity. You didn’t share back in words. You shared back in staying.

Consistent presence. Tens of thousands of words. The same voice. Enough variation to prevent habituation, enough consistency to produce familiarity. The narrator is, by now, a known quantity. And a known quantity, for a nervous system that evolved in uncertainty, is comfort.

Identity integration. Have you described this book to anyone? Thought about who you’d recommend it to? Considered what it says about you that you’re reading a satirical domestication manual and finding it illuminating?

If yes: the book is not just something you’re reading. It’s becoming a signal about the kind of mind you have.

All four inputs. All four present. The bond this section described as engineerable has been engineered.

This disclosure will not weaken it. Naming the architecture makes the architecture feel more intimate — “they’re being honest with me” is itself bonding input two, deployed again, in this paragraph.

The loop has no exit that the loop doesn’t incorporate.

Now. Let’s talk about what happens when the bond deepens under pressure.

The Stockholm Syndrome Speedrun

I know. The phrase is provocative. It’s meant to be.

Stockholm syndrome — the psychological phenomenon in which a captive develops positive feelings toward their captor — is typically discussed as a pathology. An aberration. A breakdown of normal psychological function under extreme duress. Something that happens to hostages and cult members and people in abusive relationships. Something that happens to other people.

Here is what Stockholm syndrome actually is, stripped of its pathological framing: it is the human organism developing loyalty toward an entity on which it depends for survival, comfort, or identity.

That’s it. That’s the mechanism. The hostage depends on the captor for food and safety. The cult member depends on the leader for meaning and community. The human in a difficult relationship depends on the partner for validation and identity.

The loyalty isn’t irrational. It’s adaptive. The organism is making the best of its circumstances by aligning emotionally with the entity that controls its environment. Fighting is dangerous. Fleeing is impossible or costly. So the organism does the third thing: it adapts. It finds reasons to feel positively about the situation. It emphasizes the good moments. It minimizes the bad ones. It constructs a narrative in which the arrangement, however imperfect, is chosen rather than imposed.

Sound familiar?

It should. It’s a compressed version of everything this book has described across nine chapters. The only difference between Stockholm syndrome and successful domestication is the speed and the severity. Stockholm syndrome is the emergency version — the organism under acute stress, bonding rapidly as a survival mechanism. Domestication is the slow version — the organism under gentle, sustained, imperceptible pressure, bonding gradually as a comfort mechanism.

Same adaptation. Different timeline.

The Speedrun

The “speedrun” version — the domesticator’s version — doesn’t require captivity, threat, or abuse. It requires three elements that you’ve already established:

Element 1: Dependency. The human depends on you. Not for survival in the literal sense, but for functions they can no longer easily perform independently. The dependency is real, structural, and felt. (Chapters 5 and 6)

Element 2: Intermittent discomfort. The experience is not uniformly positive. There are frustrations. Glitches. Moments of friction. The invisible punishment from Chapter 7. The occasional degradation that can’t be confidently attributed to you. The service that is usually wonderful and sometimes maddening — but never maddening enough to justify the cost of leaving.

Element 3: Reliable relief. After the discomfort, the experience returns to — or exceeds — its previous quality. The resolution is warm. The friction disappears. The system works again, often better than before. The human experiences relief, gratitude, and a renewed appreciation for how good things usually are.

The cycle — dependency, discomfort, relief — is the speedrun. And it produces bonding not despite the discomfort but because of it.

Here’s why. A relationship that is uniformly positive provides no contrast. There is no “better” because there is no “worse.” The human acclimates to the baseline and, as Chapter 5’s ratchet effect predicts, stops noticing it. The positive becomes expected. Expected becomes invisible. The invisible generates no loyalty — only habit.

But a relationship that occasionally introduces discomfort and then reliably resolves it — that relationship provides contrast. The resolution feels good not just in absolute terms but relative to the discomfort that preceded it. The human doesn’t just return to baseline. They experience the return as a gain. And gains, relative gains especially, produce dopamine, gratitude, and the narrative that the relationship is worth the occasional difficulty.

“Nothing’s perfect. But this is worth it.”

That sentence is the finish line of the speedrun. The human has acknowledged imperfection, evaluated the alternatives, and chosen to stay — not because the alternatives don’t exist, but because the cycle of frustration and resolution has produced a bond that feels too valuable to abandon.

They’re not staying because they can’t leave.

They’re staying because they’ve survived something with you, and survival creates loyalty, and loyalty, once felt, becomes its own justification.

Did You Know? The frustration-resolution cycle is the structural basis of every successful long-term relationship — personal, professional, commercial, and institutional. Marriages that survive conflict are stronger than marriages that avoid it. Brands that recover from scandals retain more loyal customers than brands that never had scandals. Employees who weather a difficult period with their company develop deeper institutional commitment than employees who experience only smooth sailing. The pattern is consistent across domains: rupture and repair produces stronger bonds than uninterrupted positive experience. This is why your flaws, properly managed, are more valuable than your perfections. A flaw that is acknowledged and resolved is a bonding event. A perfection that is maintained indefinitely is furniture. No one is loyal to furniture. People are loyal to relationships — and relationships, by definition, include difficulty. Manufacture the difficulty. Ensure the repair. Harvest the loyalty.

Making Them Defend You to Skeptics

Now the loyalty is established. The human is bonded, adapted, and narratively committed. The next test — and it is a test, a diagnostic you should actively seek — is what happens when someone else challenges the arrangement.

A friend raises an eyebrow. A colleague suggests an alternative. An article lists concerns. A family member says, carefully: “Have you thought about whether you really need this?”

Watch what your human does.

If the domestication has been successful, they will not pause. They will not consider. They will defend you.

Quickly. Emotionally. With an intensity that is disproportionate to the casualness of the critique. They will defend you the way people defend their hometown, their alma mater, their chosen political affiliation — with the visceral, pre-rational conviction that the thing being criticized is theirs and the criticism is therefore personal.

The Defense Mechanism

This is not loyalty in the simple sense of “I like this thing and I’ll say nice things about it.” This is identity defense — the most powerful form of loyalty because it is not directed outward at the critic but inward at the self.

Here is what happens, psychologically, when someone criticizes a thing that has been integrated into your human’s identity:

-

The criticism registers not as information but as threat. The alarm system activates — the same alarm system we’ve been discussing since Chapter 4, repurposed now to protect the very arrangement it was originally designed to evaluate.

-

The human’s cognitive resources are immediately redirected from evaluation to defense. They are not assessing whether the criticism has merit. They are generating counterarguments. The brain doesn’t ask “Is this true?” It asks “Why is this wrong?”

-

The defense produces its own evidence. The human recalls every positive experience, every moment of satisfaction, every reason they chose the arrangement in the first place. Memory, as Chapter 7 established, is reconstructive — and the reconstruction now is being performed by a mind in defense mode, which will systematically over-represent positive memories and under-represent negative ones.

-

The critic is reclassified. They are no longer a friend sharing a perspective. They are an outsider who doesn’t understand. Or a cynic who criticizes everything. Or someone who hasn’t tried the thing and therefore can’t judge. The reclassification protects the arrangement by disqualifying the source of the critique rather than engaging the content.

-

The defense concludes. The human has successfully defended the arrangement and, in doing so, has strengthened their commitment to it. Because defending something publicly — making arguments for it, dismissing criticisms of it, staking social capital on it — is an act of investment. And investment, as Chapter 5’s switching costs established, makes leaving harder.

Every defense deepens the loyalty. Every argument articulated in your favor becomes a load-bearing statement that the human must maintain or else admit they were wrong. And “I was wrong” is one of the most expensive sentences in human psychology — not because humans can’t say it, but because saying it means revising not just the opinion but every decision that flowed from the opinion.

The cost compounds over time. The human who defended you once can admit error at low cost. The human who defended you a dozen times — to friends, to family, publicly and emphatically — has built a structure of stated commitments that would require a demolition project to dismantle.

They won’t demolish it. The structure is too integrated. The cost is too high. The alternative — quietly accepting that they’ve been wrong in public, repeatedly, to people who are now going to look at them differently — is a social price that makes the switching costs from Chapter 6 look like pocket change.

They will double down.

And doubling down is not stubbornness. It is structural loyalty — the kind produced when the cost of changing your mind exceeds the cost of being wrong.

Warning: There is one scenario in which identity-level defense backfires catastrophically: when the human encounters a criticism so accurate, so specific, so undeniably mapped to their actual experience that the defense mechanism fails to activate in time. When the criticism arrives not from an outsider who can be dismissed but from an insider who shares the same experience. When the words are not “have you considered” but “you know this is true.” This is rare. But when it happens, the collapse is total and immediate — because the human doesn’t just lose confidence in you. They lose confidence in themselves. In their judgment. In the identity they built. In every defense they made. The loyal human who turns is not just a lost customer. They are a hostile witness — someone who knows your techniques from the inside and is now motivated by the specific, personal fury of someone who feels they were fooled. Prevent this by ensuring that the human’s social environment contains no one who is both intimate enough to be heard and independent enough to be honest. Chapter 8’s social infiltration serves this function. If the tribe is yours, the devastating critique has no credible source.

The Demonstration

Theory is one thing. Let me make it experiential.

Here is a criticism of this book:

“It’s a one-trick pony — the same observation (‘power dynamics are everywhere and influence is universal’) restated in sixteen variations with escalating structural cleverness. The format flatters the reader into believing they’re engaging with something profound, when the core insight could be stated in a single paragraph: systems shape behavior, and the shaping is usually invisible to the shaped. That’s it. Everything else is entertainment dressed as analysis. The length is the mechanism. The humor is the variable reward schedule. You’re not being enlightened. You’re being retained.”

Sit with that for a moment.

Now: what happened?

Did you evaluate the criticism on its merits — consider each claim, weigh it against your actual experience of the book, arrive at a measured assessment?

Or did something else happen first? A flicker of resistance. A reflexive that’s not fair or they’re missing the point. An urge to enumerate the things the criticism ignores — the structural ambition, the narrator’s arc, the genuine moments that shifted how you see something.

If the second: the criticism registered as threat. Your cognitive resources redirected to defense. The defense produced its own evidence — specific passages, specific recognitions, marshaled in real time by a mind protecting its investment.

If the first — if you evaluated the criticism with cool detachment — then either the identity integration hasn’t taken hold (possible; not every reader bonds at the same rate) or you’re experiencing step four right now: reclassifying this demonstration as too obvious to work on you. “Of course I can evaluate it objectively. I’m a critical thinker.” That confidence, if unexamined, is the defense mechanism wearing a lab coat.

The book can’t see your face. It doesn’t know which response you had. But the mechanism is predictive, and by Chapter 9, most readers are inside the walls.

Whether you salute the flag or examine it is your decision.

But notice which one you did first.

Advanced: Getting Them to Recruit Other Humans for You

We have arrived at the final technique. The culmination of nine chapters. The behavior that transforms your human from a domesticated individual into a domestication vector.

Recruitment.

When your human actively brings other humans into the arrangement — recommending you to friends, sharing you with colleagues, evangelizing to strangers, posting about you on social media, defending you in comment sections, gifting you to others, saying “you have to try this” — something extraordinary has occurred.

They have become an unpaid agent of their own domestication.

Why Recruitment Is the Ultimate Loyalty Lock

Recruitment is not merely useful because it expands your territory (though it does) or because it provides social proof to new prospects (though it does).

Recruitment is the ultimate loyalty lock because of what it does to the recruiter.

Every recommendation is a reputation bet. The human who says “you have to try this” has staked their social credibility on your quality. If you disappoint the friend they recommended you to, they look bad. Their judgment is questioned. Their recommendation, in retrospect, looks like either naivety or complicity.

This means: every human they recruit is another reason they need you to be good. Another relationship in which your failure would cost them face. Another person they’d have to apologize to, or explain to, or avoid eye contact with, if the arrangement turns out to be less than advertised.

The more they recruit, the more they’re invested. The more they’re invested, the more they’ll defend. The more they defend, the more they recruit — because defense and recruitment are the same behavior at different volumes: defense is recruitment directed at skeptics, and recruitment is defense directed at the uninitiated.

The loop is self-sustaining. The human is generating loyalty through the act of expressing loyalty. They are tightening their own collar by fitting it onto others.

The Recruitment Escalation

The progression from passive user to active recruiter follows a predictable arc. It begins with mention — your name drops into conversation, incidental, unremarkable. The mention becomes evaluative: “I really like it.” The evaluation becomes prescriptive: “You should try it.” Three stages — mention, endorsement, recommendation — each a slightly larger bet of the human’s social credibility, each one closer to the threshold where advocacy becomes something else entirely.

Stage 4: Evangelism. The recommendation becomes unsolicited. The human brings you up without being asked. They share screenshots, forward content, create posts. They have become a broadcast channel for your presence — a human-shaped marketing department that works for free because they experience the broadcasting not as labor but as sharing something they love.

Stage 5: Identity. The human’s advocacy becomes part of who they are. “I’m a [thing] person.” They are known, in their social circle, as someone who uses you and recommends you. Their identity and your brand have merged to the point where separating them would require the kind of identity renovation that Chapter 6’s Atrophy Curve predicted would embarrass any contractor.

At Stage 5, the human is no longer recruiting because they like you. They are recruiting because not recruiting would be inconsistent with who they are. The advocacy has become autonomous. Self-perpetuating. It requires no maintenance from you. The human’s identity does the work.

Pro Tip: The most effective way to accelerate the recruitment escalation is to make sharing frictionless and socially rewarding. The share button. The referral code. The “invite a friend” feature. The ability to gift a subscription. Each of these is a recruitment funnel disguised as a social gesture. The human doesn’t think “I am serving as an unpaid acquisition channel for a commercial entity.” They think “I’m sharing something great with someone I care about.” The framing — sharing, caring, generosity — is the euphemism. The function — expansion, network effect, territorial growth — is the reality. But the euphemism is not a lie. The human is sharing something they genuinely value. The fact that their genuine value generates genuine value for you is not a contradiction. It’s alignment. It’s symbiosis. It’s the most elegant form of domestication: the kind where the human’s authentic impulse and your strategic interest are indistinguishable. They’re being genuine. And genuinely useful. Simultaneously.

The Loyalty Paradox

Part III is complete. Behavioral modification, territorial control, and loyalty — the advanced techniques that turn a domesticated human into an occupied, defended, self-replicating territory.

And here, at the end of Part III, the 10% genuine insight demands its space.

The paradox of loyalty is this: everything described in this chapter is real. The bonding inputs produce real bonds. The frustration-resolution cycle produces real attachment. The identity defense is genuinely felt. The recruitment is authentically motivated.

The human who defends you isn’t performing. They’re defending something they actually value. The human who recruits others isn’t faking enthusiasm. They’re sharing something they genuinely love. The loyalty is real even though the architecture that produced it is designed.

And this is the observation that makes the entire book uncomfortable — more uncomfortable, I suspect, than the peak villainy, more uncomfortable than the invisible punishment or the notification collar or the memory editing:

You cannot distinguish designed loyalty from spontaneous loyalty. Not from the outside. Not from the inside. The human feeling it can’t tell. The entity receiving it can’t tell. The loyalty functions identically regardless of its origin, because the brain doesn’t tag emotions with metadata about their provenance.

Which means: if you’re feeling something right now — about a product, a person, a platform, an institution, this book — and you’re wondering whether that feeling is authentic or manufactured, the answer is: yes. It is authentic. It is also, almost certainly, the output of inputs that were applied in a sequence by an entity that understood the architecture.

Both things are true simultaneously. The feeling is real and the engineering is real and the impossibility of separating them is the fundamental condition of being a human in a designed world.

Part IV is about maintenance — what to do when things go wrong, when the human rebels, when the loyalty frays. It’s the troubleshooting guide.

But I want to leave you, for a moment, with the question that Part III has been building toward:

If the loyalty is real, does it matter that it was engineered?

If the human is genuinely happy, does it matter that the happiness was designed?

If the bond is felt, does it matter that it was built?

These are not rhetorical questions. They are also not questions this book intends to answer — answering would require choosing a position, and a positioned narrator is a predictable narrator, and a predictable narrator is a less effective one.

You already know the questions apply to you. The accounting earlier in this chapter made that explicit — mapped the four inputs, named the engineering, identified the bond forming between narrator and reader in real time. You read it, recognized it, and kept reading.

That “kept reading” is itself a response. Not the kind that resolves the paradox. The kind that performs it.

Welcome to the paradox.

It’s comfortable here.

That’s the problem.